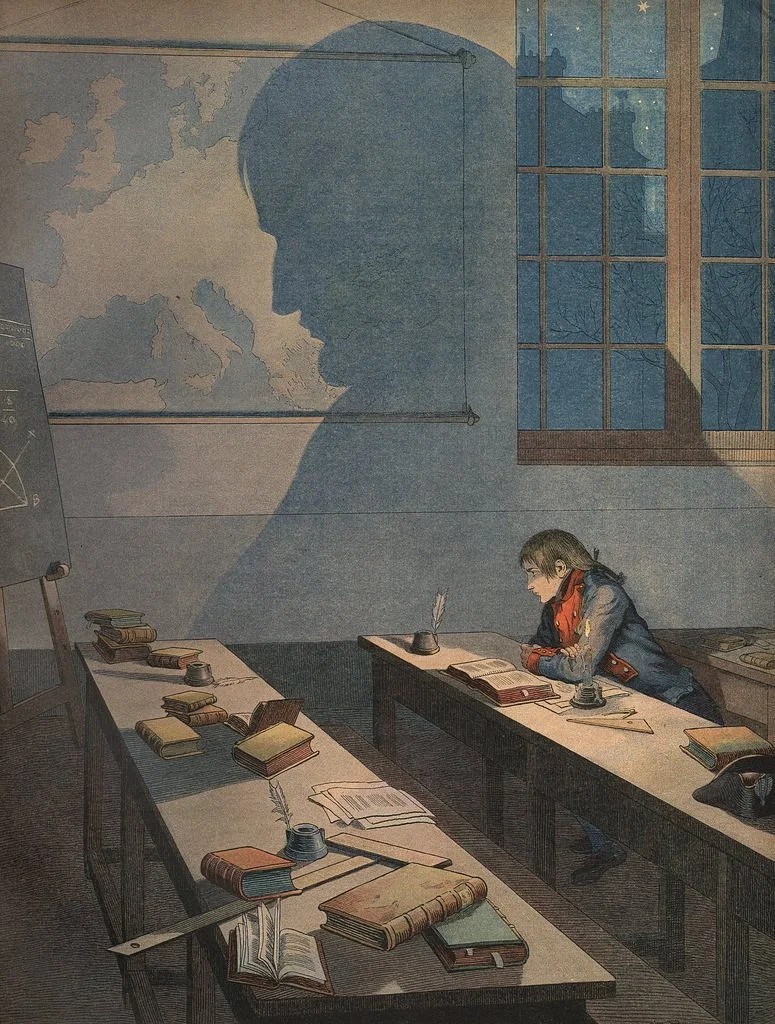

In the quiet pages of Charles Darwin’s 1836 notebook, a chilling observation appears. While standing on Australian soil, watching the interaction between white settlers and Indigenous people, he wrote:

“…the thoughtless aboriginal, blinded by these trifling advantages is delighted at the approach of the white man, who seems predestined to inherit the country of his children.”

Darwin was not recording a policy or a crime. He was observing what he believed to be a biological inevitability. To him, displacement appeared almost prewritten—predestined. The “fitter” power arriving to take its place.

Nearly two centuries later, as we watch the devastation unfold in places like Ukraine, we are forced to ask an uncomfortable question:

Have we evolved at all, or are we still trapped inside a 19th-century understanding of “survival of the fittest”?

The Misuse of “Fitness”

Darwin arrived at his conclusions through observation—through nature, through ecosystems, through the cycle of life. In the natural world, the “fittest” is not always the strongest or the most aggressive, but the most adaptable.

Somewhere along the way, humans distorted this idea.

We took a descriptive theory and turned it into a moral justification.

In the hands of modern political power, “fitness” has come to mean dominance. Resources, weapons, endurance—who can last the longest, who can impose their will most effectively. When a country uses its immense power to crush another, this is not evolution. It is a choice.

And we are choosing it repeatedly.

We funnel billions into warfare while healthcare systems crumble, food shortages persist, and entire populations live in precarity. We are choosing to be fit for war rather than fit for life.

The Modern Jungle: Social Darwinism in Disguise

The predestination Darwin observed did not disappear. It simply changed locations.

Today, it lives in boardrooms instead of battlefields.

We’ve sanitised the language of conquest. We talk about “hostile takeovers,” “crushing the competition,” “winning markets.” This is Social Darwinism dressed in professional attire—the belief that for one person, company, or country to succeed, another must lose.

Success becomes vertical rather than expansive. Measured by height, not depth. By how far we stand above others, not by how much value we create.

When we normalise pulling others down as “just business,” we are not evolving—we are reenacting the same logic Darwin recorded in 1836, only now with better technology and higher stakes.

The False Necessity of War

There is a familiar argument that war is necessary—that conflict creates momentum, forces innovation, and drives progress. History does show that wars accelerate technological development. But empowerment at what cost?

Lives are lost on both sides—human lives that mean very little to the people dictating warfare from a distance. Political power struggles have been reduced to contests of endurance. This war is not serving the people of Ukraine. Whatever the outcome, it will simply reflect who stayed “strong” the longest.

Strength has been confused with suffering.

A Biological Detour

There is something else that keeps bothering me.

Humans are not biologically designed to live in a constant state of survival.

Yes, we can survive. We are resilient, adaptive, astonishingly capable. But survival was meant to be temporary—a response to immediate danger, not a permanent operating system. The human nervous system is built to return to safety, connection, creativity, and rest once the threat has passed.

Chronic survival does not make us stronger. It makes us reactive. Fearful. Tribal. It shuts down empathy and narrows perception. Neuroscience shows this clearly. Prolonged fight-or-flight degrades the very capacities that make us human.

So why is this ideology of survival continually promoted as the engine of human evolution?

Because survival mode is easy to control.

Fear simplifies narratives.

Fear collapses nuance.

Fear makes domination feel necessary.

Darwin saw the white man as “predestined” to inherit the land—but that destiny was written in gunpowder, not DNA.

War is not a biological necessity. It is a failure of imagination.

Redefining Fitness

Darwin described what he observed. What we do with it is our responsibility.

Humans are the only species capable of reflection—of choosing differently. If survival is the only metric we optimise for, we may continue to exist, but we will never truly evolve.

Perhaps the truly “fit” are not those who survive at the expense of others, but those evolved enough to realise that survival is no longer the goal.

The real question is no longer who survives—

but who dares to imagine a world where survival is not the price of progress.

And whether we are brave enough to live it.