Paulo Freire once nailed it: true literacy isn’t just about reading the word, but reading the world. That means looking beyond the text and into the systems, the power plays, and the hidden agendas that manufactured that text in the first place.

And let’s be honest, this kind of intellectual excavation is most urgently required when we crack open the accounts we lazily call “history.”

The Lies We All Agreed Upon

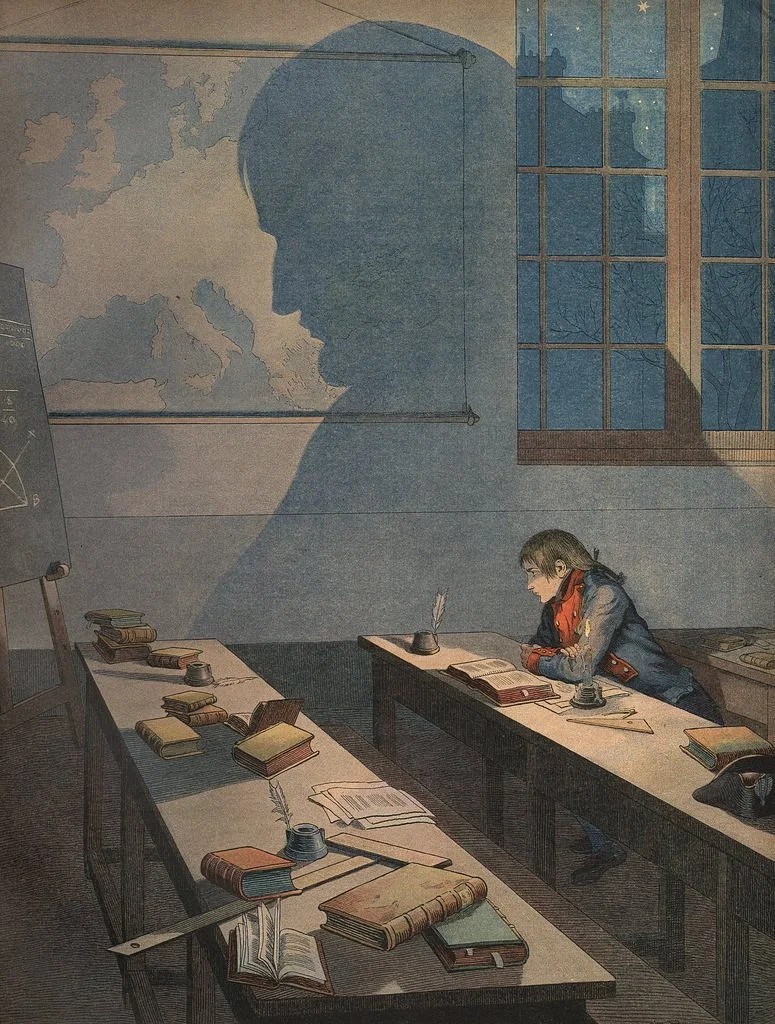

Napoleon Bonaparte famously declared, “History is a set of lies agreed upon.”

It sounds like a cynical, high-level tweet. But the more you sit with it, the more ominous it becomes. Because when the folks with power write history, they aren’t writing a mirror for you to learn from. They’re writing a memoir—a meticulously edited, self-flattering, career-justifying memoir.

Napoleon proved this point on St. Helena, where he spent his final years mythologizing himself as a tragic hero, a visionary crushed by global fear. And the world? We just shrugged and accepted it. His version became the nation’s framework, and his self-portrait was adopted as their identity.

This is where Freire’s warning hits hardest.

When we inherit a compromised story, the lie becomes the foundation. We stop seeing history as a record and start treating it like a ghost map—a map drawn by the conqueror that shows only the boundaries they want you to respect, not the messy reality of the land itself.

The Problem With Hand-Me-Down Propaganda

The real punch in Napoleon’s quote isn’t that he lied, but that we collectively agreed to call it the truth.

History filtered through the powerful is a subtle, pervasive tool for control. When people—especially those historically marginalized—inherit the tales written by their oppressors, they unconsciously absorb the worldview that justifies their own limited position. They grow up unable to tell the difference between objective patriotism and high-budget propaganda.

If the history we start with is distorted, the lesson we pull from it is corrupted. And if the lesson is corrupted, the future we build is structurally flawed. This is precisely why entire societies keep repeating the same spectacular failures, just in trendier outfits. When the story is broken, the cycle is inevitable.

My own obsession with memory and truth comes from this very tension. Memory is always edited. Identity is always curated. History is always a negotiation. A nation remembers what makes it look good and conveniently forgets what makes it accountable. And wherever collective memory has a blind spot, future generations are left carrying inherited delusions as if they were established facts.

We Owe Honesty to the Future

Freire argued that liberation starts with critical consciousness—the willingness to question every tale, to unlearn every inherited illusion, and to “read the world” beneath the tidy surface. If we don’t do this work, we aren’t remembering history; we’re just running the script again.

The main imperative, then, isn’t to track down the elusive, perfect historical truth—that ship probably sailed—but to rigorously commit to the truth right here, in the present moment.

We don’t owe perfect clarity to the past. We owe honesty to the future.

If our children are going to build a smarter world, they can’t use our myths as blueprints. They deserve analytical clarity, not heroic self-narratives. They deserve a history that isn’t afraid to name its own shortcomings.

To “read the word and the world” is to hold both warnings at once: the stories we agree upon shape our societies, and only a commitment to truth keeps us from reliving the cycles we pretend we’ve outgrown.

Let’s commit to leaving behind fewer lies than we inherited. Only then will the next generation read the world not as it was edited for them, but as it actually is.